The 300 Year Party

Published: August 2021

Imagine taking a magic carpet ride through northern Europe from east to west in Biblical. The area is circled on the map shown below — an area that Ugo Bardi rather unkindly refers to as a "vast regions of fog and swamps, inhabited by hairy Barbarians . . . the area we call today "Western Europe".

You would fly from what is now western Russia, over the Ukraine, Belorussia, northern Germany and France, and on to England and Eire. Looking down from the airplane you see a continuous forest with a scattering of clearings and villages, and just a few towns — very small by modern standards. These isolated settlements would be connected by a few narrow roads, tracks and footpaths.

Were you to make the same airplane journey today you would see fields, towns, large cities, railways, airports and freeway-style roads. Only a vestige of the primeval forest remains. Why? What happened in the last 2,000 years to cause such a dramatic change in the landscape? Why have the forests disappeared?

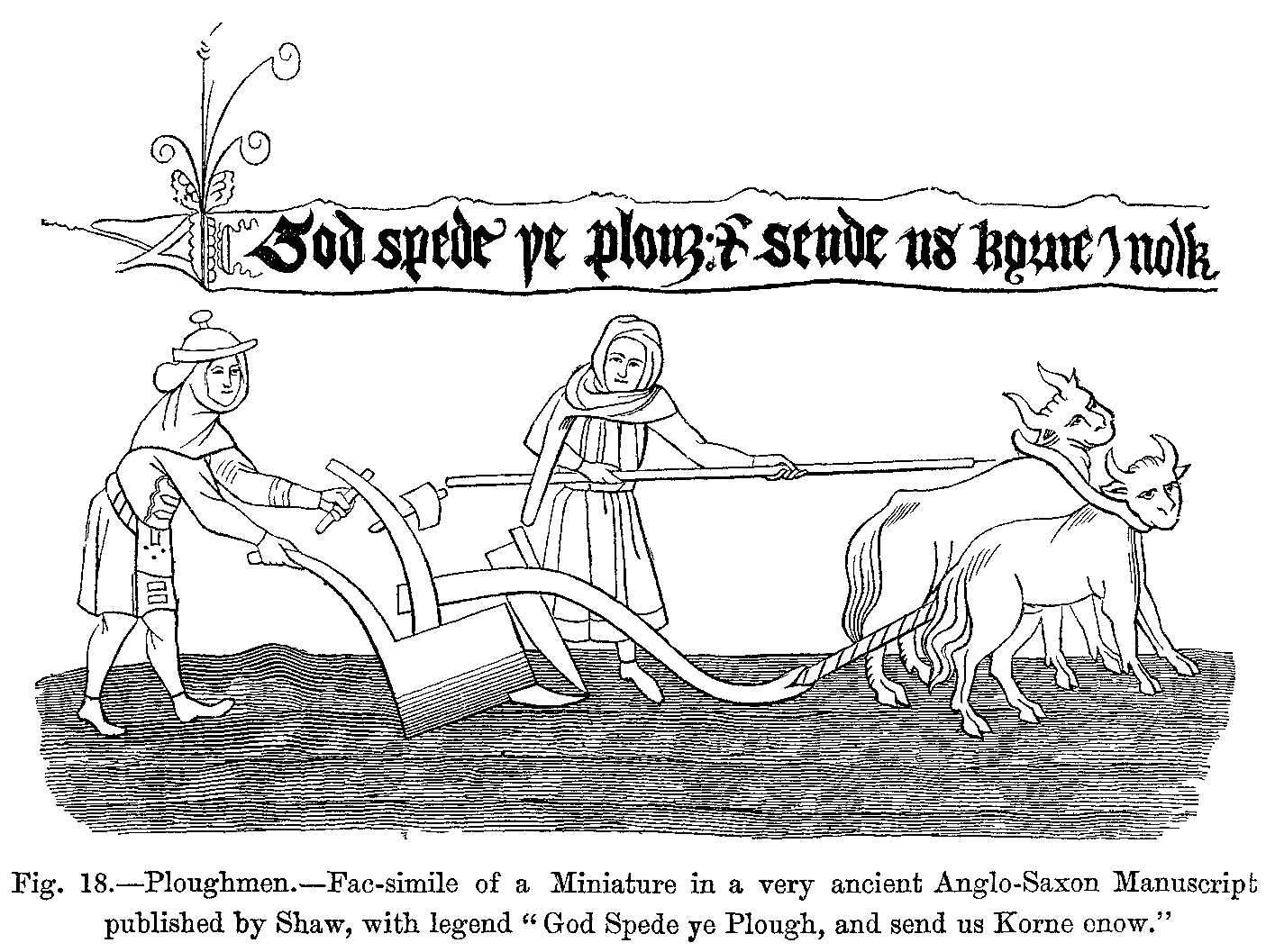

One answer to the above question lies in the nature of the soil and climate. The soil of northern Europe is generally heavy, and the climate is cool and wet. Consequently it is difficult to plow the soil and grow crops. But sometime in the 7th to 9th century CE (a period of time that we ironically refer to as the Dark Ages) the heavy cross plow was developed.

Up until that time plows had been based on a Mediterranean design. They were designed to create a shallow furrow in light, dry soils. Therefore they are easy to pull; generally two oxen or horses were more than sufficient. Also, because the team was small and because the plow was light, it was fairly easy to turn around and plow the next furrow in the reverse direction. Hence the fields were square in shape.

This type of plow did not work so well in the wet, heavy soils of northern Europe. The heavy cross plow was much more effective. It had a vertical knife with an iron cutting edge, a horizontal share to slice under the sod, and a moldboard to turn the sod over. However, this type of plow was heavier than the Mediterranean-style plow and required much more effort to pull, so teams of up to eight oxen were needed. Turning the team was difficult and required more space than the Mediterranean system, so the fields were no longer square, they now tended to consist of long, narrow strips.

But first the trees had to be cut down, which they were, thus leading to the relatively open landscape of western Europe compared to Biblical times.

The effectiveness of the new plow resulted in gradual deforestation so that more land could be opened up for growing crops. The additional crops that could now be produced led to population growth, and also to to changes in the way society was organized. For example, surplus food meant that more people could now move to the towns and work in activities that did not directly contribute toward agriculture. Also, because few peasants could afford eight oxen or own their own plow, they had to pool their equipment to form communal teams. Consequently, society gradually came to be organized around the demands of this new technology. Indeed, the heavy iron plow can be seen as being one of the precursors to the industrial revolution, both technologically and socially.

The deforestation and opening of agricultural space created a vicious cycle. The forests were cleared, more crops were produced, the population grew, so more land was needed to feed the increased number of people, so more forests were cleared and so on and so on. Eventually, of course, a limit was reached; once the forests had been mostly cleared there was no more new arable land to exploit. The picture below shows the North York Moors in northern England — an area now regarded as a place of natural beauty. Actually, the original, natural beauty of this area is forest, not moorland.

Deforestation had a second outcome. Society was using up its supply of wood. Wood was absolutely crucial to mediaeval civilization — not just as a source of heat, but also as the material of construction for buildings, tools and equipment — virtually everything was made by wood, including, of course, the cross plow itself (only its cutting edges were made of iron).

So the people of the late Middle Ages were faced with a conundrum: there is little new arable land and their vital raw material is disappearing. What do? By the year 1700 an answer was urgently required. They were running out of wood, and of cleared land needed to grow food. Their answer, just like ours now, was to find and develop alternative fuels. In their case, the obvious source of energy that could replace wood was coal.

Buried Sunlight

What we refer to, somewhat inaccurately, as “fossil” fuels are really buried sunlight. Over the course of many millions of years plant life died and sank to the bottom of lakes and the oceans. A tiny fraction of this material was compressed at high temperatures and slowly formed coal, oil, natural gas. The first of these gifts from ancient times to be exploited was coal.

Coal was not a new source of fuel; people of the middle ages had been using it for many years as a source of heat for their homes. However, most of that coal was “surface coal”, i.e., it was taken from surface seams or from the beaches (sea coal). But there was insufficient surface coal to meet the needs of the developing industrial economy — hence it became necessary to extract coal from underground mines. But, as we have seen, the countries of northern Europe generally have a wet climate and a high water table, hence the new coal mines were often flooded. Some means of pumping the water out of the mines was needed. To do this they needed two technological devices. They needed high capacity pumps to remove the water and they needed engines to power those pumps. Hence, necessity being the mother invention, the industrialists of that time had to invent the steam engine.

Thomas Newcomen was a Baptist preacher and iron worker. He developed a steam engine to pump water from the Cornish tin mines around the year 1710; his invention was quickly adopted by the coal-mining industry. The essential point here is that men such as Newcomen did not invent these machines because they felt like it; demonstration steam engines had been invented two thousand years earlier but they had never been commercialized. He and other like him developed industrial-scale steam engines (which were fueled by the coal that had just been mined) because the economy of the time needed them. The forests were "past peak". (Strictly speaking Newcomen's machine was an atmospheric engine, not a steam engine because the power stroke came from air pressure driving the piston. It was also horribly inefficient — at the end of the power stroke water was injected into the cylinder, which then needed to be reheated. But it had one important engineering attribute: it worked. How it worked is shown in this YouTube animation.)

However, simply digging coal out of the ground was not sufficient. Most coal mines are not near the factories and communities that need the coal. The transportation system of the time consisted of wooden carts, hauled by horses along muddy roads. The solution was to turn the newly-invented steam engine through 90 degrees, put the engine on a frame, put the frame on wheels, and put the wheels on steel rails. In other words, the solution was to invent the railway. Which means that we have just started the Industrial Revolution. The 300-year party started. It was coal that put the “Great” in “Great Britain”.

Oil

The discovery and exploitation of coal was followed by even more important developments for oil and natural gas.

The oil industry in the United States started in the year 1859 when Colonel Drake (who wasn’t actually a colonel) drilled a commercial well in Titusville, Pennsylvania to a depth of about 70 feet. (He is the person in the stovepipe hat in the picture below.)

Production was around 25 barrels per day. His important innovation was the use of casing pipe with a drill inside it rather than just digging a hole. The pipe prevented the well from collapsing. It also meant that there was no effective limit as to the depth of a well. Drill pipe is still the technology used by the oil industry. The subsequent oil boom in Pennsylvania meant that, until the discoveries in Spindletop, Texas, at the turn of the 20th century, the Pennsylvania fields were producing more than half of the entire world’s oil.

Happy Motoring

Although the industrial revolution started with the exploitation of coal reserves early in the 18th century, it was only with the onset of the oil industry that our modern, high-consumption lifestyle really kicked into gear, particularly in the years following the Second World War. We entered the era of “Happy Motoring”. It is this era that is now coming to an end.

Another consequence of Newcomen’s invention was the creation of the chemical industry. At first coal was used primarily for heating, but the hydrocarbon molecules that make up coal are very complex and can be used as the building blocks of many other chemicals.

End of the Party

The last 300 years have been unique in human history. We learned how to dig up buried sunlight — the remains of creatures that died millions of years ago. This wonderful resource has provided us with an equally wonderful lifestyle. Our use of so much “buried sunlight” led to unprecedented economic growth and material abundance. This, in turn, led to the creation of a new human faith system — one that is shared by people all over the world. Regardless of where they live or what their religious beliefs may be, most people believe in non-stop material progress. Such a faith system would have been incomprehensible to the people living prior to the 300-year party.

We are like a person who has inherited a lot of money and who can, for a short period of time, live luxuriously and extravagantly. Once the money is gone, it is gone. So it is with fossil fuels — once they are gone they are gone. We are returning to a time when, once more, our lifestyles will have to be truly sustainable. New sources of energy such as solar panels and wind turbines can help slow the rate of decline, but they do not replace fossil fuels. The 300-year party is coming to an end — the fossil fuels are running out and there is no easy substitution. Industry and society in general will have to learn in a Net Zero environment, i.e., a world without fossil fuels.

Copyright © Sutton Technical Books. All Rights Reserved. 2021.